Reaping the Rewards of Diversity through Team Development

Several months ago I was sitting in a circle of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) professionals discussing the power of diverse teams. Naturally, we were all listing the benefits of diversity in our own organizations. That’s when our facilitator said:

“The thing about diverse teams is that they aren’t more successful; they actually underperform. Unless, they engage in team development. Then they outperform non-diverse teams.”

Her central argument was simple. When we are different from one another, we are more likely to have opposing points of view which leads to conflict. Without appropriately establishing norms and boundaries, getting to know each other, and setting mutual goals, team members may find themselves coming into conflict so much they can’t move together towards high performance.

This argument highlights our collective cultural (see: American) fear of conflict. We shy away from people who are unlike us because we fear clashing with them, even when so much of the business thought leadership today emphasizes that healthy conflict drives more innovation and better results.

As someone who not only works on a diverse team, but also facilitates change in both homogenous and diverse teams, I started investigating how conflict specifically manifests on diverse teams, which ultimately led me to apply conflict management principles and models in several different company systems. Here’s what I found.

How Conflict Manifests on Diverse Teams

Humans evolved with “toward” and “away” responses. We move towards those who are like us (friends) and away from those who are different (perceived foes). We are so primed to associate with one another based on the similarity that even the smallest shared social identification brings us together and amplifies the likelihood of intergroup bias. In other words, the “us and them” impulse is strong.

There are a number of early childhood studies that show this dynamic at play. For example, a 2011 study found that five-year-olds randomly grouped with other unfamiliar children by the color – red or blue – preferred pictures of children wearing the color that corresponded to their own groups.

As Mapping Innovation author Greg Satell points out, these preferences manifest in adults, too. In a study of adults randomly assigned as “leopards” or “tigers,” fMRI studies noted intergroup bias and hostility towards the other group, regardless of race.

In other words, bias requires both a sense of similarity and of difference. The perceived difference may breed hostility and conflict.

So, does that mean diverse teams are destined to underperform unless they can find common ground? Not exactly.

There is a body of evidence showing that homogenous teams underperform precisely because they are more “comfortable” environments, while diverse teams outperform due to the increased effort necessary to work within them.

As David Rock, Heidi Grant, and Jacqui Grey emphasize in their 2016 HBR analysis, homogeneous teams collaborate easily and understand each other inherently… and also are prone to make the wrong judgments.

For example, in a 2009 study of fraternity and sorority members published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, fraternity and sorority members who are more likely to self-select into groups based on similarity and a strong sense of shared group identity engaged in an experiment to solve a murder mystery. Teams either remained homogeneous throughout the experiment or introduced “outsiders.” Homogenous teams reported feeling like they were progressing more smoothly and collaborating more effectively, while the diverse teams found the experience harder, and the participants felt less confident in their final decisions.

And yet, the homogenous teams made the wrong judgments, getting the answer right only 29% of the time. Groups with outsiders arrived at the correct solution 60% of the time. The work felt harder and the outcomes were more likely to be successful.

In other words, we are more fearful of outsiders and tend to find collaboration harder with them at the very same time that we produce better work through that partnership.

The conflict we experience in more diverse teams is precisely why we see better results on them.

We just have to make sure that conflict isn’t so explosive that collaboration stalls completely.

Strategies for Managing Conflict

“Four things that do not come back: the spoken word, the sped arrow, the past life, and the neglected opportunity.” Ted Chiang, Exhalation

When it comes to conflict, I have a natural accommodation preference. I have an almost pathological need to make everyone happy, and I will neglect my own needs or pursue the wrong path if I imagine it will lead to good vibes. On a diverse team, this means that I personally feel wiped out during collaborations and can shy away from the conflict necessary to get us to an amazing final product. And I’m a DEI practitioner!

Consequently, I’ve had to learn behavioral modifications that allow for me to fully be present with conflict and manage it so that I can engage with it healthily. I can’t pretend to be 100% perfect in this practice, but I can say that I’ve made noticeable progress with the tools I’ve developed.

Namely, after looking at years of collaboration in multiple types of groups, I’ve come up with four principles for managing (not eliminating) conflict on teams.

- Conflict management is about looking for a mutual goal. At the beginning of team development, we all align on one goal we can get behind. Our thinking, strategies, processes, and practices may all be different and divergent after that point, but we will have an anchor to ground us and remind us of the value of fully engaging with each other in collaboration, no matter how challenging it may feel.

- Healthy conflicts involve parties who respond rather than react. Emotional regulation is essential to healthy conflict. That means creating enough mental space for oneself to assess a situation and intentionally mobilize energy before engaging.

- Conflicts end with a decision. This means clearly stating what is going to happen, even if it’s “Agree to disagree.” The decision can be not to change or to pursue a new path. It simply must be explicitly stated and recognized in the group.

- The conversation doesn’t end with the conflict resolution. Once conflict on a team is resolved, I have observed a tendency (including my own) to avoid team members for fear that somehow the conflict will start over. However, this approach allows for the conflict to reopen, especially based on a feeling that “We aren’t talking so something must be wrong.” Bonding after strain and struggle leads to a deeper connection.

Above the Line/Below the Line

Whenever I share these conflict management principles with teams, I am inevitably met with full support of principles 1, 3, and 4. The idea of responding rather than reacting, though, feels out of reach for many of the teams I coach and facilitate.

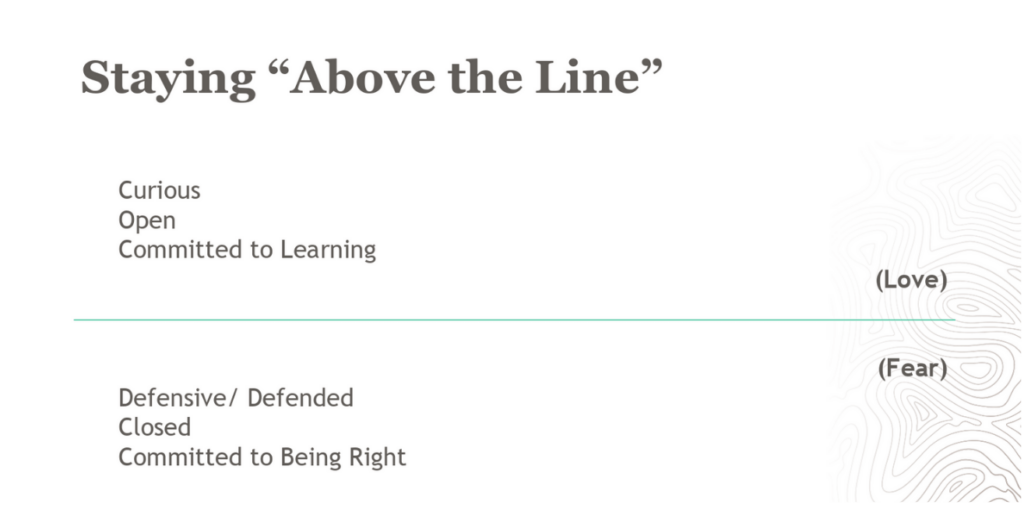

That’s why I highly recommend keeping the Above the Line/ Below the Line exercise close to you. It’s surprising how focusing on this simple framework can so quickly bring you back to neutral.

Put simply, if you’re above the line, you’re coming from a place of openness, curiosity, and commitment to learning. If you’re below it, you’re defensive, closed off, and committed to being right. It’s natural to vacillate between the two throughout a single conversation. The key is to notice when the change happens and take a step back.

When conflict starts to feel out of hand, and you notice yourself getting heated, simply take a pause and ask these four questions:

- Am I “above the line” or “below the line”?

- What is being threatened here?

- What am I thinking that this conversation says about me?

- Has my top priority shifted to preserving my ego?

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve personally used this question cycle to get back to a place of learning and improve my ability to listen, understand, and collaborate in a heterogenous (and really any) group.

Parting Words

There’s a moment in Lisa Halliday’s novel Asymmetry that for me, truly embodies the power of a diverse group on learning and understanding. The protagonist in the section entitled “Madness” is an Iraqi-American who is much more culturally American than Iraqi. In visiting relatives in Iraq, he stumbles into an argument about New Year’s Resolutions.

When laying out the basic premise, his relative says, “Who are you… to think you can control your behavior in the future?” The answer to this seems logical; you can ostensibly eat more vegetables and run the track, right? She replies by emphasizing that in Iraq, bombings could make leaving the house impossible, and the overall political climate could make for massive food shortages. So, no, running the track and buying vegetables in the future may not be in your control.

While they fail to fully convince each other, their mutual love allows them to continue talking.

Years later, our protagonist is finally in a situation where his status as being from an “enemy culture” overrules the privilege of being American, and he truly can’t predict or control his own behavior. He reflects on this idea, and it shapes his perception of the situation. In my interpretation, he is more equipped to handle a truly mad detainment because he came into conflict with an opposing view with his relative previously.

We shouldn’t be afraid of the conflict that might arise from coming up against another culture or social identity-shaped worldview. Instead, we should look for the opportunity to learn something that helps us better understand our world and engage with it differently as a result.