[00:45:53]

Yael:

It’s not just we need to take care of ourselves first because the world is on fire. But it’s certainly true that it’s not also about we can’t go out trying to put out the fires of the world when you are on fire. And so, it has to be this inter-grieving activity that you are not separate from the world, and so caring for yourself and caring for the world are the same thing.

[Music plays]

Alida:

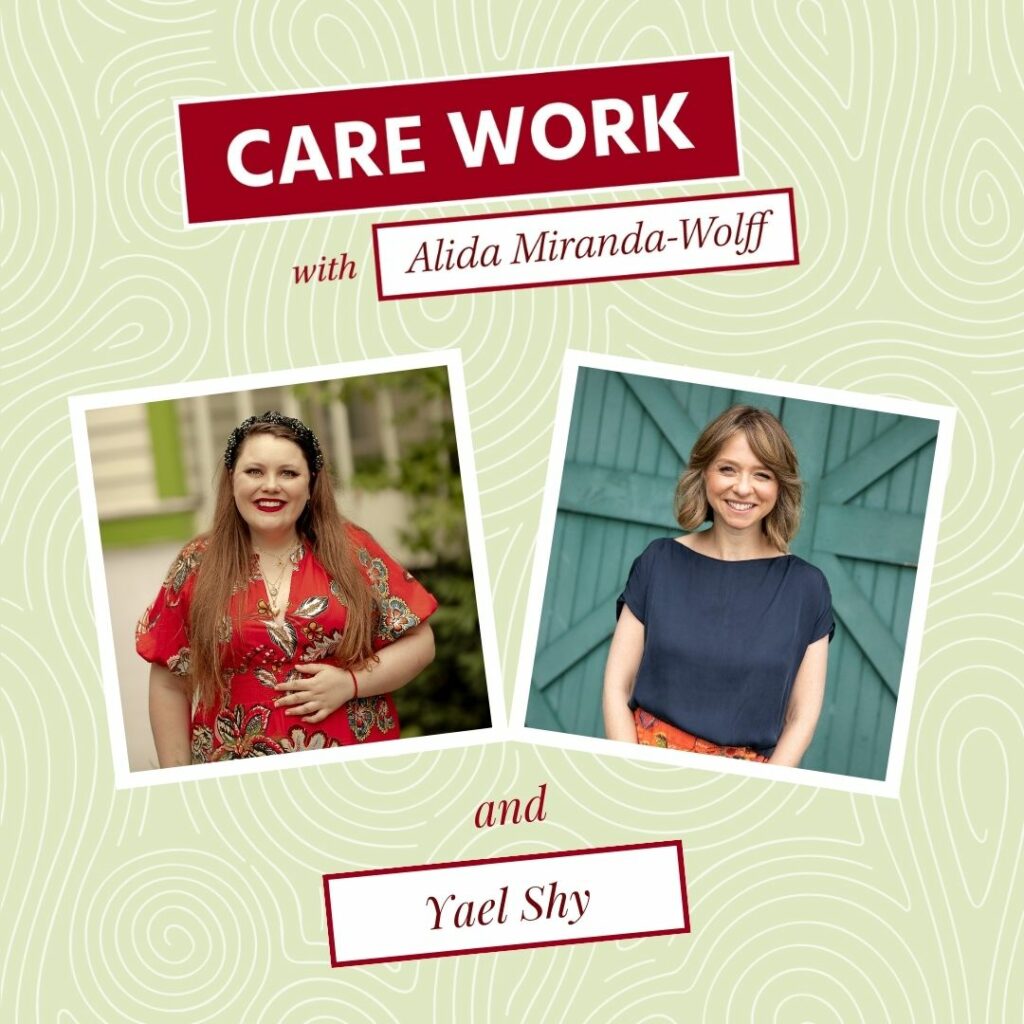

Welcome to the Care Work podcast. I’m your host Alida Miranda-Wolff and for the last ten years as a diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging practitioner I’ve focused on providing care to other people for a living. This is a podcast about people like me, care workers. I explore with a host of guests what it means to offer care and to take care of ourselves in the process.

Yael Shy’s life purpose is to support individuals and collectives in uncovering their inherent worth and capacity for deep joy. She has been using the transformative power of mindfulness rooted in 20 plus years of study in Judaism and Zen Buddhism over the course of her career to support herself and others through the pressures of life.

Yael wrote the award-winning book What now? Meditation for your 20s and beyond, and teaches at NYU’s Wagner School of Public Service. She also founded Mindful NYU, which is the largest campus-based meditation program in the country. In our conversation we reminisce as Yael happens to be one of the people who has most influenced my life and my professional inclinations.

We talk about the importance of tending to our wounds and what it means to care for yourself and care for the world as something that is connected rather than separate. And we make sure to end with some actionable tools and tips for folks looking to connect to their sense of healing.

Welcome, Yael! I’m so excited to see you again. The last time I saw you I think I was eight months pregnant, and we were working on movement-based meditations together as it was necessary since sitting with my own breath was nearly impossible as I could not breathe–

Yael:

[Laugh]

Alida:

and was so uncomfortable seated. So, it’s a different time now and I am just so looking forward to hearing more about what has been happening in your life, but also sharing some of the invaluable lessons that you’ve taught me as my mindfulness and meditation coach with listeners today.

Yael:

I’m so happy to be here, it’s so good to see you again.

Alida:

Well, in thinking about this podcast I immediately thought of you because really what we are trying to do together is to build a unified theory of what care work is. But practically. So, you know, care work is often talked about in terms of health care or it’s talked about in terms of feminist politics as when we think about who does the work of caring for people. It tends to be people from marginalized genders and all of that is very interesting to me, it’s very much part of my research and scholarship. It also doesn’t help with the actual doing of the care work, [Laugh] and that is something I really wanted to bring in to this conversation because not only are you a care worker yourself, but you teach people how to take care of themselves, which is a little bit different than other kinds of care workers. And so, I really wanted to start at the very beginning and ask you how you came to this world of mindfulness and meditation, especially because this happened for you relatively early on in your life.

Yael:

Yes, it did and it’s such an interesting take on care work and on taking care of oneself. I came to meditation when I was in college and I was just really suffering. And you know, I had panic attacks and a ton of anxiety, just a lot of things in my life were coming to a point where I could not really handle them anymore. I couldn’t walk around in the world. I was just, you know, I was incapacitated frequently throughout the week. And it’s a strange thing that I’m sure, you know, people listening might identify with, that I still managed to get decent grades and to get my assignments in on time, but internally I was really falling apart.

And my mother happened to have.. she saw a flyer for a meditation retreat. I had not meditated before and that’s where I started meditating on this seven day long, completely silent meditation retreat outside of instructions and asking your questions of the teacher. And so, it was crazy deep dive into the deep end, dropping into the deep end. But it changed the course of my life. So, right of the bat I started understanding more about my anxiety and I started kind of shifting the way that I understood my own suffering and the suffering of the world and that began the journey. So, I just kept going back, I kept learning more until I became a teacher and a meditation coach.

Alida:

What I think it’s so interesting about your story is you found meditation as a student and then as I understand it you built your career supporting students, specifically at NYU. And I wonder what that experience was like, specifically helping students take this on as a practice. And if it maybe changed the kinds of techniques you use or how the practice took shape.

Yael:

That’s an interesting question. I definitely think it’s relevant, it’s not an accident that I somehow found myself, not just, you know, at a university. At the same university that I was at when I was having a total breakdown, meltdown every single day. I came back to NYU after getting a Law degree and doing some other things. And then I began working directly with students on building this meditation community – Mindful NYU – at NYU. And I’m sure part of it was kind of healing for me to come back to the scene of the crime, the place where I was so unhappy. And a lot of the factors that kind of contributed to that unhappiness in the outside world hadn’t changed. So, for instance, I was anxious about the world. You know, when I was young it was like 911 and terrorism or whatever at that time. And then there’s other things to be anxious about in the world and, you know, there are always things to be anxious about in the world. And, then the city, New York City is expensive as it was back then. It is like very difficult to make friends and connections as it was back then.

But then, coming in as an adult, I just kind of had so many more tools. And so, I think it was really healing both for myself personally to return to this place with more tools and then also I LOVE people in their twenties and thirties. I just feel like the mind is so smart, their minds are so smart, but they are not fully crusted over with like a lot of cynicism. And yeah, things you have to kind of chip away to unlearn, that’s my experience. So, I love, love, love that population and it was so fun. I still, well I’m no longer at NYU. I run my own company called Mindfulness Consulting. I still teach at NYU, and I consult there and just that population is very close to my heart.

Alida:

When you think about students, and what they end up needing from meditation, is it different than other groups of people?

Yael:

I think just any stage or every stage and season of life is different and I think that people in their twenties particularly are often a little bit more exploring, like deeper questions about themselves and this is just generalizations, like they are often away from parents. Even when they live at home they are like away from parents for longer periods of time and so there is often more just trying to figure it out for themselves. What is this life about? For themselves. And I think it was my experience and I think it is the experience of a lot of the students that I work with that that comes along with a lot of uncertainty. Like the ground is constantly shaking, cracking beneath your feet and you are like: “Whoa, what is this world that I’m in. I’m now an adult. I’m responsible but I…” It’s kind of like the inside, you know, when a caterpillar becomes a butterfly and they become goo first and totally dissolve inside of this chrysalis. That’s what I think students feel like. Like they are becoming goo. And they are not yet a butterfly, but they are not a caterpillar, and they are in this in between stage. So, I think it’s a fertile time for transition and growth, and change. But it’s also replete with loneliness and anxiety and disorientation.

Alida:

I can’t help myself because I think it’s such a beautiful question that I want to ask it, and you can come at it in any way, but you said: “Students are figuring out what life is about”. And I’m just wondering now – Do you know what is life about?

Yael:

[Laugh] Oh, I hope not. That would be like, I feel like that’s an end of life question because I hope it’s always approaching what is life about with curiosity and I think I have some data in my body now that gets me a little closer, and helps me feel aligned with the right kinds of clues of what life is about for me.

So, you know, for me my answer to that question is I think life is about authentically unfolding in the way that every single person is meant to unfold in their authentic way and is meant to offer their gifts in their way, that only they can do. And I think there is a strong current of something to do with love. Offering love, remembering that we are here to give love and to remember that we are kind of lovable and made of love. I think that’s part of what life is about for me. [Laugh] But I’m very clear to qualify that because I don’t know what other people’s experiences are. That’s just what I’m noticing for me.

Alida:

It ties in really nicely this authentically unfolding idea with how you describe people in the chrysalis becoming goo. There is a process of becoming that I think really underlies everything that you talk about. And it brings up for me just how I came to you and your work overall, which was when I was twenty-four years old my colleague at work Steven Ross bought me a book. And it was What Now? and it was on sale at the Meditation Space, which is no longer open, but was across from our office. And he looked at it and he thought: “This seems like something Alida would like”. Because he knew that I was doing some meditation, that I liked to go to the meditation studio, and he was trying to get something for me that was thoughtful. And I picked it up and I thought: “Okay, sure. Meditation for your 20s and 30s it seemed like it might be more participatory or active in some of the Pema Chodron and you know, the Tara Brach’s stuff that I was reading and wanted something that maybe felt more relevant to my day to day life. And I read it all in one sitting. And it very much described the state that I was in, which is a period of transition.

But also what I want to note about it, there are so many things about it that have been beneficial and viable to me since that time, but I appreciated most about the book and what ultimately drew to then seeking you out is that when I was reading it these issues or these situations that came up in my life that caused me stress or grieve or pain that other people had dismissed, you had treated with a lot of weight and gravity. And I just remember there was a moment that you talked about yourself taking a bath and meditating after having an argument with a partner and it feeling just absolutely soul crushing to be in that situation. And being in a world where you are constantly asked to think about the suffering of other people and how they are stricken and impoverished and suffering and you know, think about 911, think about the war in Ukraine. Whatever context you are in, the fact that someone could say: “You need to take a break and really tune in and offer yourself love and care without judging why you need it”. That was new. It was new. Even though I was reading all of these things about meta and loving-kindness meditation and I was in the meditation space, it was sort of the least judgmental spot describing my lived experience. And it’s why for the longest time it was the gift that I gave. So, there’s so many people in my life today, 20s and 30s who I have given that book to, who maybe this is their first time reading a meditation book period. And they said something similar to me which is: “I just feel like I saw every day experiences that I was dealing with treated as if they mattered”. And so, I wonder if you might talk a little bit more about your book and why you wrote it, what you think of it as being about. What lessons came to you as you were working on it?

Yael:

Well, first of all, thank you so much. That is the most beautiful thing and I just also want to say that I remember you so well. You came I think the second part of this is you came to my reading that I did at that studio, and you asked the most brilliant question of the entire night. And so, I remember that so much about you, just your beautiful spirit. So, the book, yes! It is so personal. It’s so funny because I didn’t even think like, I almost never thought should I be actually writing this? [Laugh] I think because all I had. I mean I’m trying to pull in a lot of Buddhism, that’s the tradition that is anchored in. The whole book is anchored in Buddhism. And I’m pulling in other types of wisdom traditions and poetry and whatever has been meaningful to me. But the central place of my, where I’m coming when I talk to people is from my own experience. And when I wrote the book, pieces of it came from other talks that I had given that were the day after or the week after those terrible, crushing moments when happened fights, being dumped, being really beset with anxiety not just about the world stuff or what.. I felt like people always condescended to me when I was that age, especially in college. They would kind of wrap up my anxiety that I felt, kind of being like: “Yeah. You got a lot of stress with your homework”. And I would be like: “I don’t even know what the purpose of being alive it”. Again, back to that. [Laugh] “And you are like, you are kind of coming at me with this stupid thing about being stressed about homework”. And I just think like that…so all the writing that I did for the book was a really alive, it was in real time or fairly quickly after it what I was experiencing and making sense of and applying these Buddhist principles into those experiences.

And that was just, you know, the scope of the book, I wrote it over a long period of time and so, I even have this little part about social justice and working towards caring for the world. But the two are just not mutually exclusive. It’s not just we need to take care of ourselves first because the world is on fire, but it’s certainly true that it’s also not about who can’t go out trying to put out the fires of the world when you are on fire. And so, it has to be this inter-grieving activity that you are not separate from the world and so caring for yourself and caring for the world are the same thing.

Alida:

What I wonder about is you mentioned that you were writing these things as it was happening in real time, and you are putting yourself out into the world. I think about the book as an act of creation, as a way of caring for the world and a way of caring for yourself because you are perhaps, and this is an interpretation, you can tell me I’m wrong, you are healing yourself by putting out those experiences, processing them, working through them, and then sharing them with other people. What was the actual act of making this thing and putting it out into the world as a kind of offering like for you?

Yael:

I think the way that I approached the writing, maybe someone told me this. I don’t quite remember, but I felt like I was writing to a friend. When I thought about what would I say to somebody who I really love and they are asking me: “What do you think about desire?” Or “What do you think about anxiety?” And if I had to really dig into my heart and in my experience and come forth with an answer, that’s how I wrote it. Actually, you are making me remember that there was an entire first draft, not of the whole book but of the first few chapters where it was much more instructional. It was like: Oh! This is what Buddhism says about these topics and my friends who I gave to read it to were like: “Yeah, take all of this out and just tell me about what this actually means to you”. And that’s what I had to do. That little moment was excruciating because I was like: “I don’t know! I’m not sure!” And then, as soon as I pulled up the stories, then it flowed and it was great. I didn’t want to think about what if other people like it or don’t like it. I just imagined I was talking to a friend, and I challenged myself to try as hard as I could to be honest. To be super duper honest about the truth of what happened, how I felt, how I feel now. And so, every time I try to.. I began to sum it up with a pretty picture and after that day I never felt sad again. I was like: Uhhh. Okay, I still feel sad, but I didn’t go to those depths again. And I tried to kind of keep coming closer and closer to the truth.

Alida:

That of course brings me to when I first sought you out which was that meditation studio Chill. I went in to see you do a reading and have my book signed and all of that beautiful event-based work. And I remember being sat in the meditation and listening to the reading and then we did about five minutes. And I raised my hand because I felt like the other questions that were being asked were from people who were farther along than I was, you know? It was all about deepening practice and there was a lot of understanding of how to reach equilibrium or balance. But there is a story in your book that I tell all the time. I credit you frequently with this, but I tell it all the time and is this, and I’m totally going to mess it up, so you correct me. But it’s this idea that the Buddha was sitting with somebody next to a tree, and that person is hit with an arrow and then the person takes out a bow, an arrow and shoot themselves with the arrow. And now there are two arrows in them and the Buddha says: “That first arrow, that arrow is pain. And there is nothing that you could have done about that. Pain is natural, it is part of our lives, it is part of being in the world, but you shooting that second arrow, that’s suffering and that was a choice that you made. Pain is not a choice, suffering is”. And I raised my hand to basically say: “I can completely understand that in theory. But in practice, I already shot myself with that second arrow. And I’m suffering right now. What do I do in that situation? I can’t undo it. I can’t just say: “Oh. I sat here and I shot myself with another arrow. What next? You know, kind of to build in a pun of your book, but what now? [Laugh] What do I do? And so I wanted to talk a little bit about what you recommended to me and how that applies to your overall philosophy because I did find it to.. not to spoil things too much, but this idea of love and care and compassion is why we ended up working together in a coaching relationship and it was something that I found to be unique to you and your style.

Yael:

Do you want to say what I said? Because I don’t exactly remember. [Laugh]

Alida:

Well, you said, you basically, you said two things. So, the first thing which resonated with me immediately because I have migraines. And so you were talking about migraines and you were saying that one of the worst things you can do when you have a migraine is to tense your face, to clench your jaw, to tighten your eyes, to scrunch up your face because you are making the migraine worse. So, even though it’s really hard when you have a migraine it’s about radical acceptance so that you can soften. It’s just about trying to soften as much as possible because the more that you tighten, the more that you resist, the more pain you will experience. And that was Part 1. But Part 2 was you told me to put my hand on my face and to just say: “I’m sorry. I’m sorry that you feel like this”. And nothing more than that. It wasn’t about justifying it or making an excuse, or ruminating, or even saying: “Feel sorry for yourself because no one else will”. It was just: “Sit with yourself, acknowledge that you are in pain, and offer yourself some very gentle and simple comfort”.

Yael:

Okay, that’s pretty good. Yeah, I think that’s right. And that story that is the Buddha’s story. I didn’t make that up at all. That’s totally out of Buddhism [Laugh]. And I believe that when he says suffering is optional what the suffering actually is is like resisting the pain. It’s that clench, emotional, physical clench in the face of the pain that then adds more pain on top. And that takes a lot of different forms. It takes the form of beating yourself up, like: “Oh, what is wrong with you? Why are you in this situation again?” Or blaming someone else sometimes: “It’s their fault”. It can go back and forth like: “No, it’s my fault. No, it’s their fault. No, it’s my fault”. It’s agony. That is the purest definition of suffering is that kind of resisting what is. And you know, the more, it’s interesting that that’s what I said, that’s what you heard that was helpful because what would you actually do if you were shot by an arrow or two? What should you do? You should tend to the wound. Like, get that arrow out of you in the safest way possible and take care of the wound that just hit you. Either once or twice. It doesn’t matter. And that is one example of the way that you can take care of the wound is to just bring that kind of compassion into your experience. And I do love touching the face, touching your heart, just being like: “Ahhh! Poor thing! Ahhh, this sucks! This is so hard. This is hard!” Or another one that I tend to do sometimes in these really hard situations, not even from a religious way, but just almost like in a kind of a way I try to be: “I am giving it over. I got nothing. This is horrible. [Laugh] I am struggling’. And if you can imagine just kind of like giving it over to the universe. If you have a religious tradition that might be a bit easier for you to be like: This is God’s. This is the world’s. I need to now care for myself, get myself a cup of tea, do what I can to stabilize and try to stop throwing more arrows and more arrows. No matter how many you’ve done before this, you can always stop adding another one.

Alida:

It reminds me of another practice that you taught me which was I was sharing with you two years later I had reached out during Covid to say: “I think I really need a mindfulness coach”. And I think I had gotten an email from you about a webinar that you were leading, and I was wondering if you did any kind of individual coaching and so, I think it was one or two sessions in and I was saying: “You know, I just have so much trouble accessing that self-compassion. People talk to me about it all the time, that you have to have self-compassion, that you have to express self-care, and I don’t know what that looks like. I don’t know what that feels like. I’m an action-oriented person. I like to write a list and do the things on the list. And I think what I said to you was: “It doesn’t feel like I’m caring for myself. It feels like I’m maintaining myself. It feels like all of this is maintenance. Like, the breathing is maintenance, and the walking is maintenance, and the baths are maintenance. But I don’t feel healed. And you said, you know, at this time of course, I had six animals, I still have six animals, to look at my cat and to just key into the feelings I had about my cat. Sort of that pure sense of love and care and adoration, and you said: “And you don’t ask that cat to do anything. That cat doesn’t need anything from you for you to feel those things about him. So, just spend some time in that feeling for your cat. And all you are doing is redirecting that back to yourself. And that was more useful than any of the self-care practices I had done before because I feel like I have this untapped well of almost infinite love for the creatures in my life that I care for, and I can think about how I care for them and say: “I really do need a fresh glass of water. Just like I would say: “Oh, you are not drinking from your bowl because the water isn’t fresh. Let me freshen that up for you, let me add some ice cubes too, you know? And so, it brings me into a kind of a two part piece which is how you found yourself becoming a coach and starting your own practice, and also what helps you develop these practices that you coach people through because it was very sort of easy, maybe easy is not the right word, but very natural for you to say: “Oh, I understand that it’s hard for you to tap into self-compassion. Let’s try this”.

Yael:

Well, first of all, your cats are also very cute. They used to wander into the frame of our virtual sessions and be very, very cute, very lovable. But I think in that particular instance I think everybody, I have yet to meet like a kind of a sociopath that can’t locate their love for something or someone.

And pets are actually like pure, almost like pure examples of that kind of love because my guess is, I don’t have any pets, my guess is you can get irritated with them, but the love is much easier to access than a partner or a parent or something worse way more complicated. And the body, love is in the body. It’s just there and so it almost doesn’t matter where the point is that you are directing the love. When you access the love, then the love comes in and it’s just there. And so, you were just sensitizing yourself to this tremendous amount of love that was already there and inhabiting your body. And the useful part, this is where I think sometimes we get awry in self-care kind of mentality is fundamentally you are not a separate self from every other thing in this entire world.

We exist in different bodies and have different lived experiences, all of that is true. But, there is no place where you can definitely cut off your contact from everybody else’s contact. We completely are interconnected to one another and we inter are together, so in the same way that like you said, caring for yourself is important when you are thinking about caring for the world and caring, love for your bunnies is in a sense the same energy of love to yourself, and so that’s kind of like what we have to keep coming back to is not believing so hard that we are a self that must be cared for separate from all other things. So, I think in my experience, coaching is teaching with another person. And it’s just kind of like deep listening for the other person’s wisdom because every person comes with what they need and their wisdom. They just need a little help sometimes to kind of pull it forth.

And I was doing that primarily on meditation retreats with people who would come on retreats and then come into meetings with me as one of the teachers and they would say: “Okay, I’m learning all this stuff in the retreat from your talks or from other people’s talks and I’m struggling in this area of my life and how do I blend the two things together?” And so, taking it kind of into the outside world, in my individual coaching and in my group coaching we always practice together and we bring in wisdom from the tradition, primarily Buddhism but sometimes other traditions. And then, it’s just a matter of being like: Okay, and how does this fit? How does this look? And letting it kind of play out in each person’s body and in each person’s life because no two people are the same. So, that’s my very roundabout answer for how I do it. It’s not exactly as science. It’s just like a lot of listening and a lot of trying things and then sometimes I think, I’m sure this was the case with us, sometimes it was: Mmm, no. That’s not it. And I feel like you were very good at telling me: I don’t think that’s quite right. [Laugh] And so, you kind of shift course and you try something else and it’s just that listening, building, growing, and unfolding together.

Alida:

When I think about you, I think a lot about words like nurture and grow and flourish. And I’m wondering for you how those things come up in your mindfulness consulting work, and how you teach people to do those things for themselves, and what you learn as you watch them go through these experiences of nurturing, growing, flourishing?

Yael:

Mm. Funny that you mention that because my program, my twelve week coaching program is called Flourish. I’ll talk about that later, maybe. For trademarking reasons I’ve been kind of thinking of other ways to say that that are more trademark-able [Laugh]. It’s hard for me because I love that word and I love that idea of what a plant does, you know? It’s not one thing. It’s so many sources that go into that pot, that that plant is in or that garden and the sources are coming from all sides and it can feel sometimes especially now as I am trying to grow some stuff that I’m like: “Oh God, nothing is changing, nothing is growing. The seeds have been seeds for so long”. And the process that we go on in group coaching or individual coaching is one of just playing, listening, testing the soil. Is it getting the right amount of sun? Is it getting the right amount of water? It’s just this kind of experiment that you do together and there are certain ingredients that just seem to really accelerate that growth. It’s like miracle grow or whatever [Laugh]. Some of that is in my experience this wisdom tradition rooted in Buddhism and some of it is a community that helps that flourishing grow and some of it is it has to be the right thing for the right person. They have to, I can never ever, I’ve had people in some of my courses that just, I don’t know why exactly they signed up. Maybe they have a little bit of an inclination for it, but then they just weren’t ready. They didn’t want to meet me there or do anything. And I don’t think they got the outcomes, and so a huge part of this has to be the person showing up and ready to go there because it’s not always fun, I would say. [Laugh] It’s not pleasant to look at the things that are very painful for you and to sit with them, and to let them in. And so, you have to be so brave and ready. It has to be the right moment in your life.

Alida:

I’m just thinking about how, and I go through this as a DEIB practitioner but in different ways. How frustrating, how challenging, how taxing it can be to hold that space for folks who aren’t ready, where you feel like you are almost at the helm of a ship and you are just trying to steer it on course, but in a room with intangible feelings and experiences. And this idea of community certainly lands with me because there is this sense of, okay, you are in this group coaching session and you are trying to guide, you are trying to hold space. But that is a great expenditure of psychic energy, emotional energy, somatic energy. Who is supporting you? What is the community that you go to when you finish a session?

Yael:

Mm. I have several. I have a therapist who I love, and I’ve had coaches, business coaches and then kind of more like leadership. I am thinking of this woman who changed my life forever, her name is Yavilah McCoy and she is extraordinary, and her coaching is kind of like how to be amazing. I don’t know what she would qualify it as. And one of the things that she taught me that really have changed a lot for me was that she gave me this kind of phrase of sitting in your hips, meaning: Are you sitting, and you can’t see me right now, but I’m sitting with my back straight for my body, not for everybody’s but with your posture, with your heart open and then really rooted in the hips. And she is like: “When you have this conversation”, like she would tell me about scary conversations, she is like, “you have to be sitting in your hips Yael”. “Did you approach this person sitting in your hips?” And I love that because I think that’s right. For me, if I’m up in everybody’s business, being like: “Oh that person looks like they are not taking it in, or that person looks like they are unhappy and they are fidgeting, or this person is not participating and not involved”. It is completely exhausting and it’s unsatisfying, and it’s doing a disservice to everybody else that’s there that is paying attention. But it’s naturally, at least in my experience especially as a pleaser by conditioning, it’s naturally where I can go sometimes.

So, as long as I, it’s a true mindfulness practice for myself, if I’m sitting in own body, then I’m sitting in a place of offering. And whether they reach out their hand and take it or not, is not my business. And that doesn’t really remarkably doesn’t feel exhausting at all. It feels like tiring in the way that a good exercise class is tiring, or like a good yoga class. Like: “Oooh! I did some work there!” [Laugh] But it doesn’t feel like stopping, or like that kind of yucky tired of when you feel like you have been in somebody else’s mind and you had no business being there. So that’s how I would differentiate that. And then, the last thing I’ll say is just that I’ve been a part of different communities and classes and had so many teachers that I feel like I’m always trying to be a part of things and learn more, and grow more, and for all my skills, and yes, to support me as well.

Alida:

On that note, before I get to my final question, I want to ask you in the spirit of learning what is the one book, I know this is hard, because I struggled with it myself, but what is the one book that you would recommend to people who live a life of care, who create cultures or communities of care that they should go out and read or listen to or download that has been really impactful for you that you think it might be impactful for them?

Yael:

So, I think I would say two, I have a hard time choosing between them. They are a little bit different. One of them is a book called You belong by Sebene Selassie, and it’s just this beautiful kind of exposition of that concept I was talking about before, about the inner and the outer being one and about belonging in general, and it’s written by this incredible meditation teacher and I just love it, I give it away all the time. It’s such a beautiful book. And the second I would say it’s much different, I think it’s what it would be classified as a leadership development book, but it’s totally spiritual and has completely changed my life and so I recommend it and give it away all the time, and it’s called The Big Leap by Gay Hendricks. And, it’s a short book but in that short book he pulls in so many life-changing concepts about the nature of time and how you choose to live in time. About the ways that we, what he calls upper limit ourselves, which is the way that we dim our success because it is a little overwhelming for us, and so we often dim our success. And this concept he talks about called zone of genius versus other zones like zone of excellence, or zone of competence. And his belief is – it’s all of our birthright to live in the zone of genius in this place where work is like flow and we are, you know, it’s beautiful and it’s kind of part of us, and you know, that’s his take on things. So, it’s just a gorgeous book and it’s short and I love it. So, those are my two recommendations.

Alida:

Well, my only question left for you is where can we find you? How can we work with you? What can we do to keep this going Yael?

Yael:

Yes! Thank you for asking. So, you can find me at yaelshy.com and my business Mindfulness Consulting is on there with my offerings, so my main offering is a 12 week group coaching program called Flourish. At the conclusion of the program you get a certificate in mindfulness practices and the next time it will be run will be February of 2023, but it will run again in the later spring. So if you miss that cohort you can always join the next one. And then I’m always teaching classes or retreats for different organizations, and it’s all listed on my website or if you are on Instagram, I’m yaelshy#1.

Alida:

Thank you so much, Yael. I have so enjoyed our conversation and I’m looking forward to sitting in my hips for the rest of my day. I’m going to be taking that away from this conversation.

Yael:

Enjoy it. It’s really fun when you do it. It’s really fun.

Alida:

Thank you.

Yael:

Thank you so much, Alida. It was really wonderful.

Alida:

This podcast is a collaboration between Ethos and Alida Miranda-Wolff.

Episodes are available anywhere podcasts are found.

Your host is Alida Miranda-Wolff.

The opening theme Vibing Introspectively was written and recorded by Logan Snodgrass.

Production assistance was provided by Sonni Conway and Miera Garcia.

All sound editing and production was provided by Corey Winter.

[End of recording] [00:45:53]