In my day-to-day work as a DEIB practitioner, I am routinely met with the “it’s not fair” problem.

Namely, groups advocating against one another within an organization because their path to success either was or is more arduous, their access to resources more difficult, or their opportunities are fewer and farther between. Noticing these disparities is essential to organizational change and the achievement of equity; focusing the discussions on what is and isn’t fair, though, can quickly turn unproductively divisive.

Perhaps the most hackneyed example of this phenomenon is the pop culture stereotype of a successful woman executive making her woman-identified direct report’s life harder because the executive had to “break the glass ceiling,” so everyone else should have to, as well. I have struggled to understand where opposition happens between non-dominant groups and how enforced scarcity leads them to fight over resources rather than coming together to demand more overall.

Through YouTube serendipity, I think I’ve found an answer: envy.

Differentiating Between Jealousy and Envy

In her long-form video essay, Envy, Natalie Wynn breaks down the differences between jealousy and envy.

According to Natalie Wynn, jealousy is a fundamentally defensive response. I am jealous because I have something I value, and I perceive you want to take it for yourself. Jealousy often occurs between three people. For example, the classic love triangle is often driven by jealousy – one member of a partnered pair experiences a threat from a third person who they believe (whether accurately or not) wants to break apart their partnership and replace them in the relationship.

Envy, in contrast, is offensive and tends to occur between two people. Envy involves wanting what someone else has and also wanting that they no longer have it. The act of wanting in of itself is not envious. In fact, that’s more aligned with greed. What differentiates envy from jealousy and greed is that being envious involves desiring another person to lose what they have.

In the beloved anime Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, the concept of envy comes to life in the form of the agender character, Envy. Envy actively destroys human life out of feelings of disdain for humans rooted in a sense of inferiority, covetousness of their social relationships and status, and a need to prove their own dominance. Unlike their counterpart—the character Greed—Envy is not satisfied to have what humans have or accumulate the wealth, status, and power they believe humans possess; they must actively harm humans and take action to obliterate the human race altogether.

This scenario plays out inside of workplaces all of the time. A person in a position of power may be jealous of an employee with less power they perceive as “coming for” their job, their ability to make decisions, their pay, or their resources. The triangle is made up of the more powerful person, the power they hold, and the less powerful person. That same person may also be envious of the person with less power, perhaps because they believe they have it “easier” or don’t have to give up as much to ascend. In this situation, the powerful person might make comments like, “It’s not fair that you don’t have to work as hard as I did to get where you are,” with the implicit message amounting to “Because it wasn’t easy for me, it shouldn’t be easy for you. In fact, you don’t deserve it at all.”

Of course, the latter example is flawed for a number of reasons.

First of all, definitions of “easy” and “hard” are generally subjective. To call into question fairness on the basis of these terms is a recipe for misinterpretation and projection that doesn’t actually account for the reality of the envied person’s experience.

Second, this kind of statement is in line with a kind of logical fallacy known as false dichotomy fallacy or black-and-white fallacy, which involves limiting the available options to two when there are actually more options available. The dichotomy in the “it’s not fair” statement is that attaining power can only happen through an easy or hard way. The reality is that there are multiple avenues to power, multiple definitions of easy and hard, and even multiple experiences of the pathway to power.

Unpacking Social Identity Envy

The idea that something “isn’t fair” plagues the discourse around social identity. More often than not, I see it coming between different non-dominant groups fighting for attention and resources. The envy around one group’s perceived privileges or advantages obscures a common goal of changing the existing power structures altogether, dividing rather than unifying groups who share the same enemy: marginalization.

There is a term for this phenomenon which is known as “Oppression Olympics.” The term is thought to be coined by Chicana feminist scholar Betita Martínez in 1993 during a conversation with Angela Davis at the University of Santa Cruz.

In their conversation, Martínez and Davis explore how different groups of color can come together to overcome institutional barriers. Martínez emphasizes that the institution itself intentionally creates divides by withholding resources from one group while providing it to another. She frames this in the context of a university.

“I don’t mean that some communities or some groups on a campus or in any other community will not want to emphasize certain needs. That’s inevitable, and there’s nothing wrong with it. But we cannot be trapped in arguing about ‘My need is greater than yours,’ or ‘A women’s center is more important than a Latino cultural center,’ or whatever. We have to fight together because there is a common enemy. The general idea is no competition of hierarchies should prevail. No ‘Oppression Olympics’!”

That same argument applies to any organization or institution. During the early weeks of the national protests sparked by George Floyd’s murder, more than one of my clients came to me with troubling “Oppression Olympics” examples. The most common was between employee resource groups (ERGs) championing different racial identities. At one company, a representative from an Asian American and Pacific Islander ERG wrote an open letter to the company CEO stating, “When you say Black lives matter, you are saying AAPI lives don’t. Where was your statement in support of us when we were being targeted as carriers of the ‘china virus’ and openly enduring racial slurs? Where was the statement from our Black colleagues?” The Black ERG wrote a response letter that retorted, “How can we be expected to stand up for [the members of the AAPI group] when you’ve never shown up for us?”

The false dichotomy fallacy, once again, rears its ugly head. This exchange can be read as either the AAPI group receives attention or the Black group does. The reality, of course, is that the company could easily issue two statements – or even three or four or five – without one group or another having to silence themselves or face scarcity. Of course, as Martínez notes, at different times, each group can emphasize different needs based on who is most impacted. It’s just that the relationship between them does not need to be adversarial; in fact, banding together and pooling resources could help them achieve gains for all employees of color at the organization.

I hesitated in sharing this example because I have no desire as a white-passing person to reinforce the narrative that groups of color are divided against each other or perpetuate their own marginalization. Let me be clear—the common enemy in this situation is an institution that decides only one group’s trauma is worth naming and supporting, effectively pitting groups against each other to “win” the visibility they need to spark change. And, just because I used this real-life example does not mean that this situation hasn’t happened amongst other non-dominant groups or even between non-dominant groups and dominant ones! I myself have fallen prey to comparative grief and unproductive vying for resources.

The point I want to emphasize is one better stated by Martínez: “What kind of coming together do we need to win these demands? And if you know the administration will pick your groups off one by one, then the largest umbrella you can possibly get is probably the best one.”

Moving Towards a “Rainbow Coalition”

Because I believe that envy is a destructive (although human and often unavoidable) force and that it is weaponized against non-dominant groups to keep them down while dominant groups can continue with business as usual, I live in a state of trying to counter the “Oppression Olympics.”

It’s a standing joke in my household that my solution to everything is to form another “rainbow coalition.”

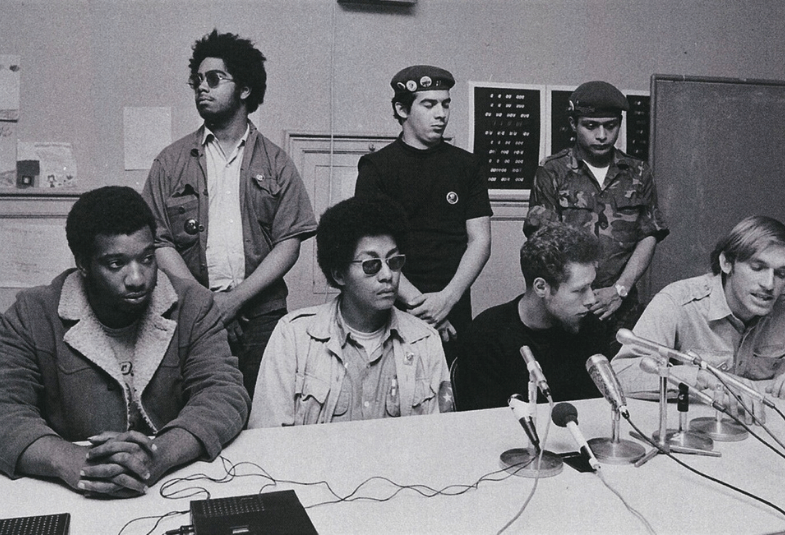

If the term rainbow coalition doesn’t ring a bell, here’s a lightning-fast recap. The first Rainbow Coalition was an anti-racist, anti-classist multicultural movement that developed in 1969 under the leadership of Fred Hampton, and since his assassination, it has evolved over time. Currently, Jesse Jackson has leveraged the original ideology and appropriate it and some of its language for his own movement through Rainbow/PUSH.

I am using the term more generally to refer to a movement rooted in solidarity rather than in competition. What a rainbow coalition as a counter to envy looks like starts with a few questions:

- When I feel envious of another person or group, where is that coming from? What is being threatened?

- Who, ultimately, is responsible for the imbalance between me and that person or group? How might this imbalance be corrected?

- Where do I experience a common cause with that person or group?

- How might I work together with that person or group to achieve that common cause?

With this framework, banding together rather than breaking apart seems more possible.

For example, those two ERGs could have identified that what was being threatened was the access to visibility, acknowledgment, and support from their peers and leaders in the face of major harm to their respective communities. The imbalance between the groups wasn’t the fault of either the AAPI or Black ERGS, but rather the organization that determined there was only room to advocate for one group (and in my opinion, only in a moment of national crisis that threatened its image). Therefore, the imbalance has to be corrected by changing the way the organization operates around issues of social identity. The common cause is the need to change the organization to offer all communities visibility, acknowledgment, and support. By working together to list out what actions need to be taken and resources accessed, the groups could come together and use their combined clout to get everyone what they needed.

Of course, the process would have been hard, and some conflict may have arisen; that’s the work of team-building. Regardless, both groups could have achieved a constructive, generative outcome that led to further change in the future.

Angela Davis says it best in her conversation with Martínez, “I think we need to be more reflective, more critical and more explicit about our concepts of community.”